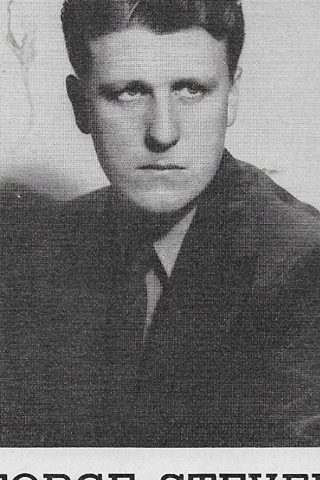

| Name | George Stevens |

| Phone |  |

| Email ID |  |

| Address |  |

| Click here to view this information |

George Stevens, a filmmaker known as a meticulous craftsman with a brilliant eye for composition and a sensitive touch with actors, is one of the great American filmmakers, ranking with John Ford, William Wyler and Howard Hawks as a creator of classic Hollywood cinema, bringing to the screen mytho-poetic worlds that were also mass entertainment. One of the most honored and respected directors in Hollywood history, Stevens enjoyed a great degree of independence from studios, producing most of his own films after coming into his own as a director in the late 1930s. Though his work ranged across all genres, including comedies, musicals and dramas, whatever he did carried the hallmark of his personal vision, which is predicated upon humanism.

Although the cinema is an industrial process that makes attributions of “authorship” difficult if not downright ridiculous (despite the contractual guarantees in Directors Guild of America-negotiated contracts), there is no doubt that George Stevens is in control of a George Stevens picture. Though he was unjustly derided by critics of the 1960s for not being an “auteur,” an auteur he truly is, for a Stevens picture features meticulous attention to detail, the thorough exploitation of a scene’s visual possibilities and ingenious and innovative editing that creates many layers of meanings. A Stevens picture contains compelling performances from actors whose interactions have a depth and intimacy rare in motion pictures. A Stevens picture typically is fully engaged with American society and is a chronicled photoplay of the pursuit of The American Dream.

George Stevens was nominated five times for an Academy Award as Best Director, winning twice, and six of the movies he produced and directed were nominated for Best Picture Oscars. In 1953 he was the recipient of the Irving Thalberg Memorial Award for maintaining a consistent level of high-quality production. He served as president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences from 1958 to 1959. Stevens won the Directors Guild of America Best Director Award three times as well as the D.W. Griffith Lifetime Achievement Award. He made five indisputable classics: Swing Time (1936), a Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers musical; Gunga Din (1939), a rousing adventure film; Woman of the Year (1942), a battle-of-the-sexes comedy; A Place in the Sun (1951), a drama that broke new ground in the use of close-ups and editing; and Shane (1953), a distillation of every Western cliché that managed to both sum up and transcend the genre. His Penny Serenade (1941), The Talk of the Town (1942), The More the Merrier (1943), I Remember Mama (1948) and Giant (1956) all live on in the front rank of motion pictures.

George Cooper Stevens was born on December 18, 1904, in Oakland, California, to actor Landers Stevens and his wife, actress Georgie Cooper, who ran their own theatrical company in Oakland, Ye Liberty Playhouse. Cooper herself was the daughter of an actress, Georgia Woodthorpe (both ladies’ Christian names offstage were Georgia, though their stage names were Georgie). Georgie Cooper appeared as Little Lord Fauntleroy as a child along with her mother at Los Angeles’ Burbank Theater. George’s parents’ company performed in the San Francisco Bay area, and as individual performers they also toured the West Coast as vaudevillians on the Opheum circuit. Their theatrical repertoire included the classics, giving the young George the chance to forge an understanding of dramatic structure and what works with an audience. In 1922 Stevens’ parents abandoned live theater and moved their family, which consisted of George and his older brother John Landers Stevens (later to be known as Jack Stevens), south to Glendale, California, to find work in the movie industry.

Both of Stevens’ parents gained steady employment as movie actors. Landers appeared in Little Caesar (1931), The Public Enemy (1931) and Citizen Kane (1941) in small parts. His brother was Chicago Herald-American drama critic Ashton Stevens (1872-1951), who was hired by William Randolph Hearst for his San Francisco Examiner after Ashton had taught him how to play the banjo. An interviewer of movie stars and a notable man-about-town, Ashton mentored the young Orson Welles, who based the Jedediah Leland character in Citizen Kane (1941) on him. Georgie Cooper’s sister Olive Cooper became a screenwriter after a short stint as an actress. Jack became a movie cameraman, as did their second son.

Stevens’ movie adaptation of “I Remember Mama,” the chronicle of a Norwegian immigrant family trying to assimilate in San Francisco circa 1910, could be a mirror on the Stevens family’s own move to Los Angeles circa 1922. In “Mama”, the members of the Hanson family feel like outsiders, a theme that resonates throughout Stevens’ work. Acting was considered an insalubrious profession before the rise of Ronald Reagan’s generation of actors into the halls of power, and being a member of an acting family necessarily marked one as an outsider in the first half of the 20th century. Young George had to drop out of high school to drive his father to his acting auditions, which would have further enhanced his sense of being an outsider. To compensate for his lack of formal education, Stevens closely studied theater, literature and the emerging medium of the motion picture.

Soon after arriving in Hollywood, the 17-year-old Stevens got a job at the Hal Roach Studios as an assistant cameraman; it was a matter of being in the right place at the right time. Of that period, when the cinema was young, Stevens reminisced, “There were no unions, so it was possible to become an assistant cameraman if you happened to find out just when they were starting a picture. There was no organization; if a cameraman didn’t have an assistant, he didn’t know where to find one.”

As part of Hal Roach’s company, Stevens learned the art of visual storytelling while the form was still being developed. Part of his visual education entailed the shooting of low-budget westerns, some of which featured Rex. Within two years Stevens became a director of photography and a writer of gags for Roach on the comedies of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy.

His first credited work as a cameraman at the Roach Studios was for the Stan Laurel short Roughest Africa (1923). Stevens was a terrific cameraman, most notably in Laurel & Hardy’s comedies (both silent and talkies), and it was as a cameraman that his aesthetic began to develop. The cinema of George Stevens was rooted in humanism, and he focused on telling details and behavior that elucidated character and relationships. This aesthetic started developing on the Laurel & Hardy comedies, where he learned about the interplay of relationships between “the one who is looked at” and “the one doing the looking.” Verisimilitude, always a hallmark of a Stevens picture, also was part of the Laurel and Hardy curricula; Oliver Hardy once said, “We did a lot of crazy things in our pictures, but we were always real.”

From a lighting cameraman, Stevens advanced to a director of short subjects for Roach at Universal. Within a year of moving to RKO in 1933, he began directing comedy features. His break came in 1935 at RKO, when house diva Katharine Hepburn chose Stevens as the director of Alice Adams (1935). Based on a Booth Tarkington novel about a young woman from the lower-middle class who dares to dream big, the movie injected the theme of class aspiration and the frustrations of the pursuit of happiness while dreaming the American dream into Stevens’ oeuvre. Before there was cinema of “outsiders” recognized in the late 1970s, there were Stevens’ outsiders, fighting against their atomization and alienation through their not-always-successful interactions with other people.

Stevens created his first classic in 1936, when RKO assigned him to helm the sixth Astaire-Rogers musical, Swing Time (1936). Stevens’ past as a lighting cameraman prepared him for the innovative visuals of this musical comedy. Through his control of the camera’s field of vision, Stevens as a director creates an atmosphere that engenders emotional effects in his audience. In one scene Astaire opens a mirrored door that the scene’s reflection in actuality is being shot on, and being keyed into the illusion emotionally introduces the audience into the picture, in sly counterpoint to Buster Keaton’s walk into the screen in his _Sherlock, Jr. (1924)_ . Stevens’ use of light in “Swing Time” is audacious. He freely introduces light into scenes, with the effect that it enlivens them and gives them a “light” touch, such as the final scene where “sunlight” breaks out over the painted backdrop. The film never drags and is a brilliant showcase for the dancing team. Rogers claimed it was her favorite of all her pictures with Astaire.

Stevens’ next classic was the rip-roaring adventure yarn Gunga Din (1939), based on the Rudyard Kipling poem. Though no longer politically correct in the 21st century, the picture still works in terms of action and star power, as three British sergeants–Cary Grant, Victor McLaglen and Douglas Fairbanks Jr.–try to put down a rampage by a notorious death cult in 19th-century colonial India.

Having learned his craft in the improvisational milieu of silent pictures, Stevens would often wing it, shooting from an underdeveloped screenplay that was ever in flux, finding the film as he shot it and later edited it. With filmmaking becoming more and more expensive in the 1930s due to the studios’ penchant for making movies on a vaster scale than they had previously, Stevens’ methods led to anxiety for the bean-counters in RKO’s headquarters. His improvisatory crafting of “Gunga Din” resulted in the film’s shooting schedule almost doubling from 64 to 124 days, with its cost reaching a then-incredible $2 million (few sound films had grossed more than $5 million up to that point, and a picture needed to gross from two to 2-1/2 times its negative cost to break even).

Studio executives were driven to distraction by Stevens’ methods, such as his taking nearly a year to edit the footage he shot for “Shane.” His films typically were successful, though, and in the late 1930s he became his own producer, earning him greater latitude than that enjoyed by virtually any other filmmaker with the obvious exceptions of Cecil B. DeMille and Frank Capra. He made three significant comedies in the early 1940s: Woman of the Year (1942), the darker-in-tone The Talk of the Town (1942) (a film that touches on the subject of civil rights and the miscarriage of justice) and The More the Merrier (1943) before going off to war.

Joining the Army Signal Corps, Stevens headed up a combat motion picture unit from 1944 to 1946. In addition to filming the Normandy landings, his unit shot both the liberation of Paris and the liberation of the Nazi extermination camp Dachau, and his unit’s footage was used both as evidence in the Nuremberg trials and in the de-Nazification program after the war. Stevens was awarded the Legion of Merit for his services. Many critics claim that the somber, deeply personal tone of the movies he made when he returned from World War II were the result of the horrors he saw during the war. Stevens’ first wife, Yvonne, recalled that he “was a very sensitive man. He just never dreamed, I’m sure, what he was getting into when he enlisted.” Stevens wrote a letter to Yvonne in 1945, telling her that “if it hadn’t been for your letters . . . there would have been nothing to think cheerfully about, because you know that I find much [of] this difficult to believe in fundamentally.”

The images of war and Dachau continued to haunt Stevens, but it also engendered in him the belief that motion pictures had to be socially meaningful to be of value. Along with fellow Signal Corps veterans Frank Capra and William Wyler, Stevens founded Liberty Films to produce his vision of the human condition. The major carryover from his prewar oeuvre to his postwar films is the affection the director has for his central characters, emblematic of his humanism.

Stevens’ second postwar film, A Place in the Sun (1951), was his adaptation of Theodore Dreiser’s “An American Tragedy,” updated to contemporary America. Released three years after his family film I Remember Mama (1948), it features an outsider, George Eastman, trapped in the net of the American Dream, the pursuit of which dooms him. Sergei M. Eisenstein had written an adaptation for Paramount of “An American Tragedy” (the title a sly reversal of “The American Dream”), but Eisenstein’s participation in the project was jettisoned when the studio came under attack by right-wing politicians and organizations for hiring a “Communist”, and the U.S. government deported Eisenstein shortly afterward. His script was unceremoniously dumped, and Josef von Sternberg eventually made the picture, but his vision was so far from Dreiser’s that the old literary lion sued the studio. The film was recut and proved to be both a critical and box-office failure.

Alfred Hitchcock maintained that it was far easier to make a good picture from a mediocre or bad drama or book than it was from a good work or a masterpiece. It remained for George Stevens to turn a literary masterpiece into a cinematic one–a unique trick in Hollywood. What was revolutionary about “A Place in the Sun,” in terms of technique, is Stevens’ use of close-ups. Charlton Heston has pointed out that no one had ever used close-ups the way Stevens had in the picture. He used them more frequently than was the norm circa 1950, and he used extreme close-ups that, when combined with his innovative, slow-dissolve editing, created its own atmosphere, its own world that brought the audience into George Eastman’s world, even into his embrace with the girl of his dreams, and also into the rowboat on that fateful day that would forever change his life. The editing technique of slow-lapping dissolves slowed down time and elongated the tempo of a scene in a way never before seen on screen.

Stevens’ mastery over the art of the motion picture was recognized with his first Academy Award for direction, beating out Elia Kazan for that director’s own masterpiece, A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) and Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly for THEIR masterpiece, An American in Paris (1951), for the Best Picture Oscar winner that year (most observers had expected “Sun” or “Streetcar” to win, but they had split the vote and allowed “American” to nose them out at the finish line. MGM’s publicity department acknowledged as much when it ran a post-Oscar ad featuring Leo the Lion with copy that began, “I was standing in the Sun waiting for a Streetcar when . . . “).

Stevens’ theme of the outsider continued with his next classic, Shane (1953). The eponymous gunman is an outsider, but so is the Starrett family he has decided to defend, as are the “sodbusters”, and even the range baron who is now outside his time, outside his community and outside human decency. Giant (1956), Stevens’ sprawling three-hour epic based on Edna Ferber’s novel about Texas, also features outsiders: sister Luz Benedict, hired-hand transformed into millionaire oilman Jett Rink, transplanted Tidewater belle Leslie Benedict, her two rebellious children and eventually her husband Bick Benedict, a near-stereotypical Texan who finally steps outside of his parochialism and is transformed into an outsider when he decides to fight, physically, against discrimination against Latinos as a point of honor. The Otto Frank family and their compatriots in hiding in The Diary of Anne Frank (1959), American cinema’s first movie to deal with the Holocaust, are outsiders, while Christ in his The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965)–subtle, complex and unknowable–is the ultimate outsider. The Only Game in Town (1970)–Stevens’ last film with Elizabeth Taylor, his female lead in “A Place in the Sun” and “Giant”–was about two outsiders, an aging chorus girl and a petty gambler.

Stevens’ reputation suffered after the 1950s, and he didn’t make another film until halfway into the 1960s. The film he did produce after that long hiatus was misunderstood and underappreciated when it was released. The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), a picture about the ministry and passion of Christ, was one of the last epic films. It was maligned by critics and failed at the box office. It was on this picture that Stevens’ improvisatory method began to take a toll on him. It took six years from the release of “Anne Frank,” which had garnered Oscar nominations for Best Picture and Best Director, until the release of “Greatest Story.” There had been a long gestation period for the film, and it was renowned as a difficult shoot, so much so that David Lean helped out a man he considered a master by shooting some ancillary scenes for the picture. The film has a look of vastness that many critics misunderstood as emptiness rather than as a visual correlative of the soul. Stevens’ script is inspired by the three Synoptic Gospels, particular the Gospel According to St. John. John stresses the interior relation between the self and things beyond its knowledge. Though misunderstood by critics at the time of its release, the film has become more appreciated some 40 years later. Stevens is a master of the cinema, and is fully in command of the dissolves and emotive use of sound he used so effectively in “A Place in the Sun.”

His last film, The Only Game in Town (1970), also was not a critical or box-office success, as Elizabeth Taylor’s star had gone into steep decline as the 1970s dawned. Frank Sinatra had originally been slated to be her co-star, but Ol’ Blue Eyes, notorious for preferring one-take directors, likely had second thoughts about being in a film directed by Stevens, who had a (well-deserved) reputation for multiple takes. His filmmaking method entailed shooting take after take of a scene during principal photography from every conceivable angle and from multiple focal points, so he’d have a plethora of choices in the editing room, which is where he made his films (unlike John Ford, famous for his lack of coverage, who had a reputation of “editing” in the camera, shooting only what he thought necessary for a film). Warren Beatty, typically underwhelming in films in which he wasn’t in control, proved a poor substitute for Sinatra, and the film tanked big-time when it was released, further tarnishing Stevens’ reputation.

In a money-dominated culture in which the ethos “What Have You Done For Me Lately?” is prominent, George Stevens was relegated to has-been status, and the fact that he had established himself as one of the greats of American cinema was ignored, then forgotten altogether in popular culture. Donald Richie’s 1984 biography “George Stevens: An American Romantic” tags Stevens with the “R” word, but it is too simplistic a generalization for such a complicated artist. Stevens’ films demand that the audience remain in the moment and absorb all the details on offer in order to fully understand the morality play he is telling. James Agee had been a great admirer of Stevens the director, but Agee died in the 1950s and the 1960s was a new age, an iconoclastic age, and George Stevens and the classical Hollywood cinema he was a master of were considered icons to be smashed. Film critic Andrew Sarris, who introduced the “auteur” theory to America, disrespected Stevens in his 1968 book “The American Cinema.” Stevens was not an auteur, Sarris wrote, and his latter films were big and empty. He became the symbol of what the new, auteurist cinema was against.

The Cahiers du Cinema critics attacked Stevens by elevating Douglas Sirk. Sirk’s Magnificent Obsession (1954), so the argument went, was a much better and more cogent exegesis of America than “Giant,” which was “big and empty” as was the country they attacked (though they loved its films). The point of iconoclasm is to smash idols, no matter what the reason–and Stevens, the master craftsman, was an idol. However, to say “Giant” was empty is absurd. To imply that George Stevens did not understand America is equally absurd. “Giant” contains what is arguably the premier moment in America cinema of the immediate postwar years, and it is an “American” moment–the confrontation between patrician rancher Bick Benedict and diner owner Sarge (Robert J. Wilke). Many critics and cinema historians have commented on the scene, favorably, but many miss the full import of it.

The film has been built up to this climax. Benedict has shared the prejudices of his class and his race. All his life he has exploited the Mexicans whom he has lived with in a symbiotic relationship on HIS ranch, giving little thought to the injustice his class of overlords has wrought on Latinos, on poor whites, or on his own family. His wife, an Easterner, is appalled by the poverty and state of peonage of the Mexicans who work on the ranch and tries to do something about it. Her idealism is echoed in her son, who becomes a doctor, rejects his father’s rancher heritage, and marries a Mexican-American woman, giving his father an Anglo/Mexican-American grandson.

While out on a ride with his wife, daughter, daughter-in-law and her child, they stop at a roadside diner. Sarge, the proprietor, initially balks at serving them because of the Latinos in their party. He backs down, but when more Latinos come into his diner, he moves to throw them out. Benedict decides to intervene in a display of noblesse oblige, and also out of family duty. Sarge is unimpressed by Benedict’s pedigree, and a fight breaks out between the hardened veteran–recently returned from the war, we are meant to understand–and the now aged Benedict. Bick first holds his own and Sarge crashes into the jukebox, setting off the song “The Yellow Rose of Texas” while he recovers and then sets out to systematically demolish Mr. Bick Benedict, the overlord. As the song plays on in ironic counterpoint, shots of his distraught daughter and other family members are undercut with the cinematic crucifixion of Bick Benedict, the overlord, by the former Centurion. After Sarge has finished thrashing Benedict, he takes a sign off of the wall and throws it on Benedict’s prostrate body: “The management reserves the right to refuse service to anyone”. This is not only America of the 1950s, but America of the 21st century. For just as Sarge is defending racism, he is also defending his once-constitutional right to free association, as well as exerting his belief in Jeffersonian-Jacksonian democracy in thrashing a plutocrat. This is a type of yahooism that Bruce Catton, in his Pulitzer Prize-winning history of the Civil War, attributed to the rebellion. There had always been a very well developed strain of reckless, individualistic violence in America, frequently encouraged, ritualized and sanctified by the state. The diner scene in “Giant” could only have been created by a man with a thorough knowledge of what America and Americans were (and continue to be). Sarge will try to accommodate Benedict, who has stepped out of his role as racist plutocrat into that of paternalistic pater familias, just as the sons of the robber barons of the 19th century–who justified their economic depravities with the doctrine of social Darwinism–did in the 20th century, endowing foundations that tried to right many wrongs, including racism, but Sarge will only go so far. When he is stretched beyond his limit, when his giving in is then “pushed too far,” he reacts, and reacts violently.

This scene sums up American democracy and the human condition in America perhaps better than any other. America is a violent society, a gladiator society, in which progress is measured in, if not gained by, violence. Yes, Sarge is standing up for racism and segregation (a huge topic after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling outlawing segregation), but he is also standing up for himself, and his beliefs, something he has recently fought for in World War II. The ironies are rich, just as the irony of American democracy, which excluded African-Americans and women and the native American tribes from the very first days of the U.S. Constitution, is rich. This is America, the scene in Sarge’s diner says, and it is a critique only an American with a thorough knowledge of and sympathy for America could create. It is much more effective and philosophically true than the petty neo-Nazi caricatures of Lars von Trier’s Dogville (2003), who are cowards. Characters in a George Stevens film may be reluctant, they may be hesitant, they may be conflicted, but they aren’t cowardly.

Another ironic scene in “Giant” features Mexican children singing the National Anthem during the funeral of Angel, who in counterpoint to Bick’s son, his contemporary in age, is of the land, to the manor born, so to speak, but lacking those rights because of the color of his skin. Angel had gone off to war, and he returns to the Texas in which he was born on a caisson, in a coffin, starkly silhouetted against the Texas sky as the Benedict mansion had been earlier in the film when Leslie had first come to this benighted land. Angel, who had experienced racial bigotry due to his birth into poverty on the Benedict ranch, had fought Adolf Hitler. He is the only hero in “Giant,” and his death would be empty and meaningless without Bick Benedict’s reluctant conversion to integration through fisticuffs.

The great turning points in American cinema typically have involved race. The biggest, most significant movies of the first 50 years of the American cinema death with race: Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1903), Edwin S. Porter’s major movie before his The Great Train Robbery (1903) and the first film to feature inter-titles; The Birth of a Nation (1915), D.W. Griffith’s racist masterpiece–which was a filming of a notorious pro-Ku Klux Klan book called “The Clansman”–in which a non-sectarian America is formed in the linking of Southern and Northern whites to fight the African-American freedman; The Jazz Singer (1927), in which a Jewish cantor’s son achieves assimilation by donning blackface and disenfranchising black folk by purloining their music, which he deracinates, while turning his back on his Jewish identity by marrying a Gentile; and Gone with the Wind (1939), the greatest Hollywood movie of all time–in which the Klan is never shown and the “N” word is never used, although the entire movie takes place in the immediate post-Civil War South–a sweeping, romantic masterpiece in which a reactionary, ultra-racist plutocracy is made out to be the flower of American chivalry and romance.

Stevens’ “Giant” was a major film of its time, and remains a motion picture of the first rank, but it was not the cultural blockbuster these movies were. Yet it more than any other Hollywood film of its time, aside from Elia Kazan’s rather whitebread Gentleman’s Agreement (1947) and Pinky (1949), directly addresses the great American dilemma, race, and its implications, and not from the familiar racist, white supremacist point of view that had been part of American movies since the very beginning. Those attitudes had been rooted in the American psyche even before the days of The Perils of Pauline (1914) serials (simultaneously serialized in the white supremacist Hearst newspapers), in which many a sweet young thing was threatened with death or–even worse, the loss of her maidenhead–by a sinister person of color (always played by a Caucasian in yellow or brown face).

A 1934 “Fortune Magazine” story about the rosy financial prospects of the Technicolor Corp.’s new three-strip process contained a startling metaphor for a 21st-century reader: “Then – like the cowboy bursting into the cabin just as the heroine has thrown the last flowerpot at the Mexican – came the three-color process to the rescue.” It was this endemic, accepted racism that Stevens challenged in “Giant,” which is at the root of America’s expansionist philosophy of manifest destiny, and which was at the root of much of the southern and western economies. Those who died in World War II had to have died for something, not just the continuation of the status quo. It was a direct and knowing challenge to the system by someone who thoroughly knew and thoroughly cared about America and Americans.

George Stevens died of a heart attack on March 8, 1975, in Lancaster, California. He would have been 100 years old in 2004, and in that year he was celebrated with screenings by The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, London’s British Film Institute, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. His legacy lives on in the directorial work of fellow two-time Oscar-winning Best Director Clint Eastwood, particularly in Pale Rider (1985), which suffers from being too-close a “Shane” clone, and most memorably in his masterpiece, Unforgiven (1992).

Details

George Stevens Keywords

George Stevens Contact Details, George Stevens Facebook, George Stevens Instagram, George Stevens Phone Number, George Stevens Cell Phone, George Stevens Address, George Stevens Whatsapp Number, George Stevens Whatsapp Group, George Stevens Email, George Stevens Phone Number 2020, George Stevens Twitter Account