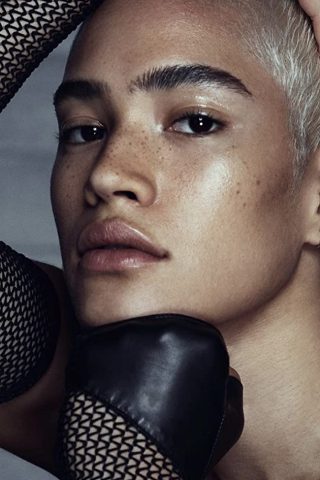

| Name | Laurence Harvey |

| Phone |  |

| Email ID |  |

| Address |  |

| Click here to view this information |

Laurence Harvey was a British movie star who helped usher in the 1960s with his indelible portrait of a ruthless social climber, and became one of the decade’s cultural icons for his appearances in socially themed motion pictures.

Harvey was born Zvi Mosheh Skikne on October 1, 1928 in Joniskis, Lithuania, to Ella (Zotnickaita) and Ber Skikne. His family was Jewish. The youngest of three brothers, he emigrated with his family, to South Africa in 1934, and settled in Johannesburg. The teenager joined the South African army during World War II, and was assigned to the entertainment unit. His unit served in Egypt and Italy, and after the war the future Laurence Harvey returned to South Africa and began a career as an actor. He moved to London after winning a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts. He then did his apprenticeship in regional theatre, moving to Manchester in the 1940s. The tyro actor reportedly supported himself as a hustler while appearing with the city’s Library Theatre. Even at this point in his life he was known to be continually in debt and adopted a firm belief in living beyond his means, a pattern that would continue until his premature death. His lifestyle would often dictate working on less worthy projects for the sake of a paycheck.

His film debut came in House of Darkness (1948), and he was soon signed by Associated British Studios. His early film roles proved underwhelming, and his attempt to become a stage star was disastrous – his debut in the revival of “Hassan” was a notorious flop. After failing in the commercial theater in London’s West End, Harvey joined the company of the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon for the 1952 season. Regularly panned by critics during his stint on the boards in the Bard’s works, he built up his reputation as a personality by becoming combative, telling the press that he was a great actor despite the bad reviews. Someone was listening, as Romulus Pictures signed him in 1953 and began building him up as a star.

Harvey was cast as Romeo in Romeo and Juliet (1954), a film that exemplified the main problem that kept Harvey from major stardom (but subsequently would serve him quite well in a handful of roles): his screen persona was emotionally aloof if not downright frigid. Despite his icy portrayal of the great romantic hero Romeo, Harvey attracted enough attention in Hollywood to be brought over by Warner Bros. and given a lead role in King Richard and the Crusaders (1954).

In Old Blighty with Romulus after his Hollywood adventure, Harvey met his future wife Margaret Leighton on the set of The Good Die Young (1954). Other film appearances included I Am a Camera (1955) and Three Men in a Boat (1956), the latter becoming his first certified hit, and even greater success was to come. The colorful Harvey, a press favorite, became notorious for his high-spending, high-living ways. He found himself frequently in debt, his travails faithfully reported by entertainment columnists. More fame was to come.

After making three flops in a row, Harvey began a brief reign as the Jack the Lad of British cinema with the great success of Room at the Top (1959). That film and Look Back in Anger (1959), which was also released that year, inaugurated the “kitchen sink” school of British cinema that revolutionized the country’s film industry and that of its cousin, Hollywood, in the 1960s.

Harvey was born to play Joe Lampton, if not in kin, then in kind. Lampton was a working-class bloke who dreams of escaping his social strata for something better. It was a perfect match of actor and role, as the icy Harvey persona made Joe’s ruthless ambition to climb the greasy pole of success fittingly chilling. In bringing Joe to life on the screen, Harvey was more successful than Richard Burton (a far better actor) had been in limning the theater’s Jimmy Porter in the film adaptation of John Osborne’s seminal “Look Back in Anger,” despite Burton’s own working-class background. Burton’s volcanic use of his mellifluous voice, a great instrument, is much too hot for the the small universe on the screen, a case of projection that is so intense that it overwhelms the character and the film (it took Burton another half-decade to learn to act on film, and a half-decade more to lose that gift). Whereas Burton had to learn to rein it in, Harvey’s already tightly controlled persona made the social-climbing Lampton resonate. Harvey fits the skin of the character much better than does Burton. Despite not being an authentic specimen, the success of his performance as a working-class man-on-the-make proved to be the vanguard of a new generation of screen characters that would be played by the real thing: Albert Finney, Tom Courtenay, Terence Stamp and Michael Caine, among others. “Room at the Top” signaled the appearance of the New Wave of British cinema. For his role as Joe, Harvey received his first (and only) Academy Award nomination.

While historically significant, “Room at the Top” is no longer ranked at the summit of other, more contemporary kitchen-sink dramas, such as Karel Reisz’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960), Tony Richardson’s A Taste of Honey (1961) and Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life (1963), or even John Schlesinger’s provincial comedy Billy Liar (1963), films that made stars out of the authentic working-class/provincial actors Finney, Alan Bates, Richard Harris and Courtenay, respectively. The virtue of the film is its emotional honesty about the manipulation of personal relationships for social gain in postwar Britain, a system that after a decade under the Conservatives had become self-satisfied and complacent. In its portrayal of class warfare, the film offers the most intense critique of the British class system offered by any film from the British New Wave, including “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning,” which never leaves the confines of the working-class strata its main character, Arthur Seaton, is stuck in and ultimately reconciled to.

That Joe chooses a woman other than the one he really loves in order to gain social mobility, engaging in emotional manipulation of other human beings, is a brutal indictment of the class structure of postwar Britain. Joe, on his way to his wedding and his great chance, has lost his humanity. His failure is symbolic of Britain’s failure as well. It is the haughtiness and narcissism of the actor Harvey (qualities his screen persona engenders in film after film) that elucidates Lampton’s weakness. A further irony of Harvey’s effective, if ersatz, portrayal of working-class Joe is that it made him such a success – he soon went off to Hollywood to play opposite box-office titan Elizabeth Taylor in BUtterfield 8 (1960), thus losing out on further opportunities to appear in the British New Wave he helped introduce. As well as supporting Taylor in her Oscar-winning turn in “Butterfield 8” (the two became close friends), a badly miscast Harvey also co-starred as Texas hero Col. James Travis in John Wayne’s bloated budget-buster The Alamo (1960).

With the exception of the lead in the British Jungle Fighters (1961)- a war picture that was decidedly NOT New Wave – Harvey did not appear again in a major British film until 1965, when he returned to the other side of the pond to reprise Joe in the “Room” sequel Life at the Top (1965). However, if he had never gone Hollywood, he might never have been cast in his other signature role: Raymond Shaw, the eponymous The Manchurian Candidate (1962). Once again, the match of actor and character was ideal, as Harvey’s coldness and affect-free acting perfectly embodied the persona of the programmed assassin. The film, and Harvey’s performance in it, are classic.

In this Hollywood interlude, Harvey also appeared in the screen adaptations of Tennessee Williams’ Summer and Smoke (1961) opposite the great Geraldine Page, Oscar-nominated for her role, and the artistically less successful Walk on the Wild Side (1962), supported by the legendary Barbara Stanwyck, French beauty Capucine and a young Jane Fonda. The critics were less kind to his acting in these outings, and, indeed, the rather elegant Harvey does seem miscast as Dove Linkhorn, the wandering Texan created by hardboiled Nelson Algren, reduced to working in an automotive garage by the exigencies of the Great Depression. Critics were even less kind when Harvey tried to follow in Leslie Howard’s footsteps in the remake of Of Human Bondage (1964).

Although he could not know it then, Harvey had reached the zenith of his career. In 1962 he won the Best Actor prize at the Munich film festival in 1962 for his role in The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962). Honors for Harvey were few after this point. He co-starred with Paul Newman and Claire Bloom in Martin Ritt’s film version of the Broadway re-envisioning of Akira Kurosawa’s cinematic masterpiece Rashômon (1950). The result, The Outrage (1964), in which Newman played a murderous Mexican bandit and Harvey his victim, was an unqualified flop that still boggles the mind of viewers unfortunate enough to stumble upon it, so outrageous is the idea of casting Newman as a Mexican killer (a role originated by Rod Steiger on the Broadway stage). Harvey, very often a wooden presence in his less inspired performances, was appropriately upstaged by the tree he remained tied to throughout most of the film.

Along with “Life at the Top,” Harvey appeared in support of Oscar-winner Julie Christie in John Schlesinger’s Darling (1965), an allegedly “mod” look at the jaded and superficial existence of what was then termed the “jet set.” Despite its “New Wave”-like cutting and visual sense, “Darling” – which was embraced wholeheartedly by Hollywood and originally had been envisioned as a vehicle for Shirley MacLaine – was, at its heart, an old-fashioned Hollywood-style morality play, a warning that the wages of sin lead to emotional emptiness, hardy a revolutionary idea in 1965. Christie was excellent – particularly as she metamorphosed from Dolly-bird to a more mature sort of hustler – and first-male lead Dirk Bogarde always proved an interesting actor, but it was Harvey who most clearly embodied the zeitgeist of the picture. Once again, his coldness did him well as he limned the executive who manipulates and is manipulated by Christie’s Diana character.

Harvey had become at this point a kind of good-luck charm for actresses with whom he appeared. Simone Signoret, Elizabeth Taylor and Christie won Best Actress Oscars after appearing in films with him, and Geraldine Page and “Room at the Top” co-star Hermione Baddeley were both Oscar-nominated in the period after appearing opposite Harvey. Alas, no one else collected kudos in a Harvey picture: he reached the high-water mark of his career in 1962, and his star was already in in decline to a murkier, less-lustrous part of the Hollywood/international cinema firmament.

Another irony of Harvey’s career is that, despite ushering in the British New Wave and a cinema more independent of the meat-grinder ethos of the Hollywood and British studios catering to popular taste, he would have been better served in the 1930s and 1940s as a contract player at a major studio. Like Michael Wilding (who also became the third husband of Harvey’s first wife, Margaret Leighton), another handsome man of limited gifts who nonetheless could be quite affecting in the right role, Harvey’s career likely would have thrived under the studio system, with an interested boss to guide him. Like Minniver Cheever, however, he was unfortunate to have been born after his time.

As it was, the next (and last) decade of Harvey’s screen life was a disappointment, with the actor relegated to less and less prestigious pictures and international co-productions that needed a “star” name. In the 1970s, Harvey became largely irrelevant as a player in the motion picture industry. His luck had run out. Good friend Liz Taylor, whose string of motion picture successes had also run its course, had him cast in Night Watch (1973), and he directed the last picture in which he appeared, Welcome to Arrow Beach (1974). If he had lived, he might have made the transition to director (he had earlier directed The Ceremony (1963) and finished directing A Dandy in Aspic (1968) after the death of original director Anthony Mann).

Laurence Harvey died on November 25, 1973, from stomach cancer. He publicly revealed that he was dismayed by being afflicted with the fatal disease, as he had always been careful with the way he ate. Sadly, his personal luck, just as capricious as his professional career, had also gone into eclipse. One of the more colorful characters to grace the screen was dead at the age of 45, exiting the stage far too soon for the legions of fans that still admired him despite the downturn in his fortunes.

Details

Laurence Harvey Keywords

Laurence Harvey Contact Details, Laurence Harvey Facebook, Laurence Harvey Instagram, Laurence Harvey Phone Number, Laurence Harvey Cell Phone, Laurence Harvey Address, Laurence Harvey Whatsapp Number, Laurence Harvey Whatsapp Group, Laurence Harvey Email, Laurence Harvey Phone Number 2020, Laurence Harvey Twitter Account